Dear Raphael Gross, dear visitors, dear guests,

I would like to begin my brief remarks with an apodictic statement:

This is a historical exhibition. And an exhibition is not a history book. Rather, it is an enactment. But what is enacted? A drama, a conflict? A scandal?

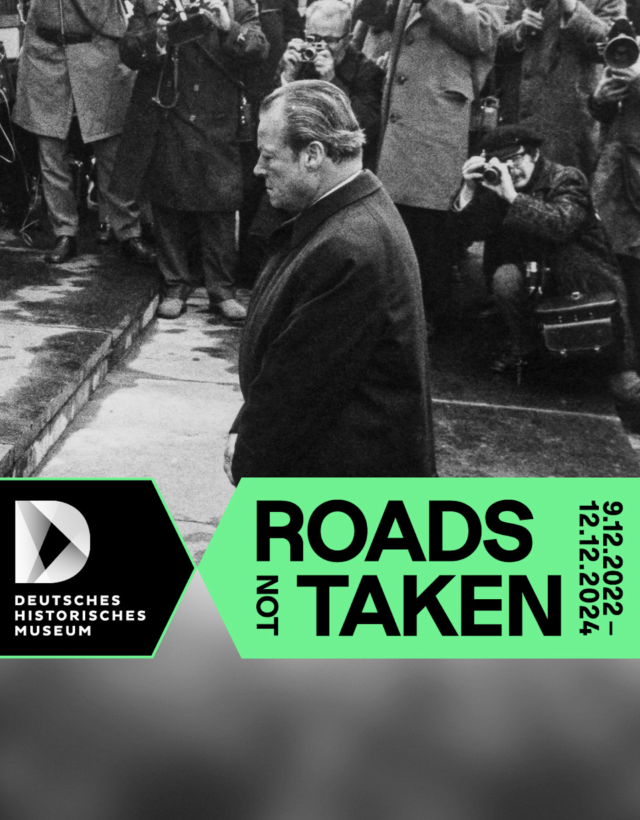

It is neither about one nor the other, but rather something highly unusual: To put it more precisely, it is about the exhibition of an argument; about a category of philosophy of history, the category of contingency. That is why the exhibition is called “Roads not Taken” – it deals with paths that have not been taken, and this under the assumption that everything could have turned out differently than it actually did. The exhibition aims to make this tension between reality and possibility visible.

In everyday language, “contingency” can be described as coincidence, turn, cut, or interruption. It’s a possible turning point that has become visible, indeed, a tangible one; one that contemporaries have at least taken note of. It’s an incision reflected in both private and public life as a cut, as a tear in one’s life plans.

People recall such cuts in their life narratives, and those born thereafter will learn of them. The associated caesura has its signs, symbols and names. Somehow, this is something we are all familiar with.

All of this also finds expression in historiography, in written history. Nevertheless, it tends to impose a context on those events that generates a meaning - and this meaning also tends to ascribe something of a necessity. In hindsight, all of those many unconnected points appear to us as an iron line. The history that has occurred and been written down as such thus seems to us to have been necessary. The counter-concept to contingency lends itself well to this: teleology. The necessary line associated with this insinuates as though that which actually occurred had to happen; as though the story had something akin to a direction, a goal, or a telos. Historiography, if only for the sake of the flow of the narrative, tends to be teleological in nature.

This exhibition intends to break with teleological perception insofar as it not only focuses on contingency, but also includes all those events, occurrences and tendencies that did not become reality.

For this purpose, it is necessary to irritate and alienate the view that is etched into historical memory. That is why we have reversed the otherwise usual historical course from the past to the present. The exhibition begins in the historical “Now”, with the fall of the Wall in 1989, and from there goes back in time to the “End Point”, the chronological “Beginning” of the year of revolution of 1848/49. The reversal of the movement of time in historical space thus aims to alienate familiar images and thus generate a heightened level of attention for what is actually known.

The reversal of the historical timeline should, among other effects, also contribute to softening the relatively ossified shell of German historical interpretation.

And beyond that, to sharpen the view of contingency and, with that, also of further possibilities that have been laid out in history, but never became reality. This doesn’t reinterpret the reality that has become historical; on the contrary. It will, however, be brought into focus as one of the possibilities presented.

It’s important to emphasise: The ground of the entered reality will therefore never leave the exhibition. In this respect, no so-called counterfactual history is presented here. One may merely lean over the parapet of the reality that has come to pass in order to recognize what was laid out and germinating far below. This is the view that the exhibition offers, and also the question that it poses.

At the centre of the exhibition are selected caesuras, which are contrasted with possible turns: Fourteen images in which reality and possibility are spatially juxtaposed, creating a tension. The argument must therefore be put forward in such a way that the audience inevitably asks itself the following question: Did it have to turn out the way it did?

Take, for example, the impressive picture of the dismissal of Reich Chancellor Heinrich Brüning in May 1932. He had requested Reich President Hindenburg to issue a further emergency decree, a fifth, which was ultimately refused. Brüning said goodbye with a speech in which he spoke of being stopped “100 meters before the finish". In addition to his efforts to reduce the reparations imposed on Germany, this also seemed to have meant his intention to navigate the country out of the economic crisis and thus to hold out until the next regular Reichstag elections, which should have taken place in the autumn of 1934. In fact, in the autumn of 1932, economists considered the trough of the crisis to have already been overcome, and society was beginning to see hope. Ultimately, however, the upturn eventually came to benefit Adolf Hitler and no longer Brüning. Hitler’s appointment as Reich Chancellor, which took place on the now iconic date of January 30th, 1933, had been unexpected at the time. In the Reichstag elections of November 1932, the NSDAP had lost two million votes. Internal disputes shook them. Hitler, who pursued a strategy of “all or nothing", threatened his supporters with suicide. When he was then appointed Reich Chancellor on January 30th, 1933, the Nazi press spoke of a “miracle”, while the Social Democratic “Vorwärts” was still talking about Hitler as a “Carnival Chancellor” on January 28th.

Or in March 1936, when Hitler undertook the militarisation of the Rhineland whilst considering it as being the ultimate risk – in the face of neighbouring France, a country possessing the most powerful continental army in Europe. In the event of a military reaction from Paris, not only would the Wehrmacht have withdrawn immediately – Hitler’s authority in the Reich would also have been massively affected, including reactions within the Wehrmacht.

What would have happened if the assassination attempt on Hitler by the conspirators of July 20th 1944 had been successful? Given the high degree of probability that Hitler could have been killed in the assassination attempt, its failure seems like a fluke, which the Nazis exaggerated in their pseudo-religious language as "providence".

The exhibition places tendencies of possibilities that weren’t able to prevail under the microscope in order to question their potential of realisation. In retrospect, the Federal Republic of Germany proves to be a highly stable period, if not the golden age of recent German history. A continuity of stability, which was nevertheless guaranteed, even from an outside perspective. It was the Cold War as a system and as a vessel of security and prosperity that ensured that stability, accompanied by the danger and dread of a nuclear apocalypse.

The year 1952 also proves to be a potential turning point, at least as far as the options presented are concerned. It was then that the Stalin Note opened up the offer of a united but neutralist Germany. The history that occurred, on the other hand, followed a different path: Instead of following national lures from the East, Bonn sought integration into the West, or more precisely, into Europe. The European Steel and Coal Community, the pursuit of a European defence community, internal burden-sharing, “reparations” for Israel... Looking back today, the year 1952 can be assessed as no less important for the young Federal Republic than the more formal founding year of 1949.

The exhibition strives for historical enlightenment as well as the strengthening of historical judgement. It intends to raise awareness of historical differences and distinctions. And it also wants to help spread democratic awareness. In this respect, it is a profoundly political exhibition.

Looking towards its own origins, the Alfred Landecker Foundation stands for the learning of lessons from history – lessons to protect democracy. And we are convinced that democratic values can be best guaranteed through the protection and support of democratic institutions.

Reality today may also contribute to strengthening judgement and historical discernment. For many visitors, the present and the Russian war within and against Ukraine might seem like a thin film over the exhibited past. This is an outlet of the “turning point”, which represents a veritable contingency in view of our expectation of history. In this way, the present encroaches on an exhibition about the past and makes it all the clearer as to what exactly its own subject matter is: The breaking in of the unexpected into a hitherto valid reality of life.

Thank you.