Antisemitism research is, contrary to popular belief, not an academic field like German studies or philosophy. It is an attempt to understand a phenomenon that goes back more than two thousand years and is now spread worldwide. The focus is on Europe – the so-called Christian Occident, dubbed “Judeo-Christian” just a few years ago. Thus the subject must be approached and understood in an interdisciplinary manner. Scholars in the social and historical sciences, literature and philosophy, theology and law, psychology and anthropology analyze worldwide antisemitic phenomena, argue about designations and definitions, about the validity of sources and arguments, approaches and hypotheses. So far, so good. But what differentiates this subject from others is its high level of politicization; the ease with which it can be instrumentalized; its identity-creating potential. This applies in every national context; but the subject of antisemitism has a very specific and often emotionally charged impact in Germany, the land of the perpetrators of the Holocaust.

Which is why the Jewish historian and Holocaust survivor Joseph Wulf, the inspiration behind the Center for Research on Antisemitism at TU Berlin – Germany’s only academic institution that focuses on this field – wanted the Center to focus on Holocaust research. After Wulf took his own life, the project he had championed over long, lonely years was adopted by the newly appointed historian Reinhard Rürup. Rürup joined with Heinz Galinski – then head of the Jewish Community Berlin and president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany – to establish the institution at TU Berlin, one of a kind in Europe.

Right away, the Center’s academic perspective was broadened to include the study of antisemitism as the underlying cause of the Holocaust. Its first director, Herbert A. Strauss, felt it was only natural that the Center consider other forms of exclusion. Anything else would have seemed not only implausible but utterly absurd to Strauss, a German-born Holocaust survivor who – like many other Jewish emigrants to the United States – had been involved in the civil rights movement and overall struggle against racism in the 1960s.

Antisemitic prejudice and other forms of discrimination

Academically speaking, this comparative perspective is not only a useful addition but also an absolute necessity in the study of the specifics of antisemitic prejudice and the ways in which it differs from other forms of exclusion and discrimination. This is just as true for the hatred aimed at Jews and Christians in antiquity as it is for early modern Spain, which expelled Jews and Muslims and – until the 19th century – even prevented their descendants, baptized for generations already, from holding state offices. It also applies to the modern era: The advocates of freedom, equality and fraternity made all kinds of excuses for denying the same rights to Jews and women.

The great promise of the Enlightenment raised the struggles for justice and equality to a new level; its enemies have since gathered behind various flags, but one ingredient has remained constant: antisemitism. Many years ago, the Israeli historian Shulamit Volkov coined the term “cultural code” to describe this phenomenon: In the 19th and 20th centuries, antisemitism served as a political bracket and identifying feature for those who postulated a basic inequality of people, whether Jews or women, homosexuals or colonized peoples. And nothing much has changed in the 21st century, as one can see in the violent attacks of recent weeks and months in which perpetrators expressed through word and deed a collective hatred of Jews, Muslims, women and democratic politicians.

We are referring to a notion of humanity that was shaped 250 years ago and that forms the foundation of Germany’s Basic Law.

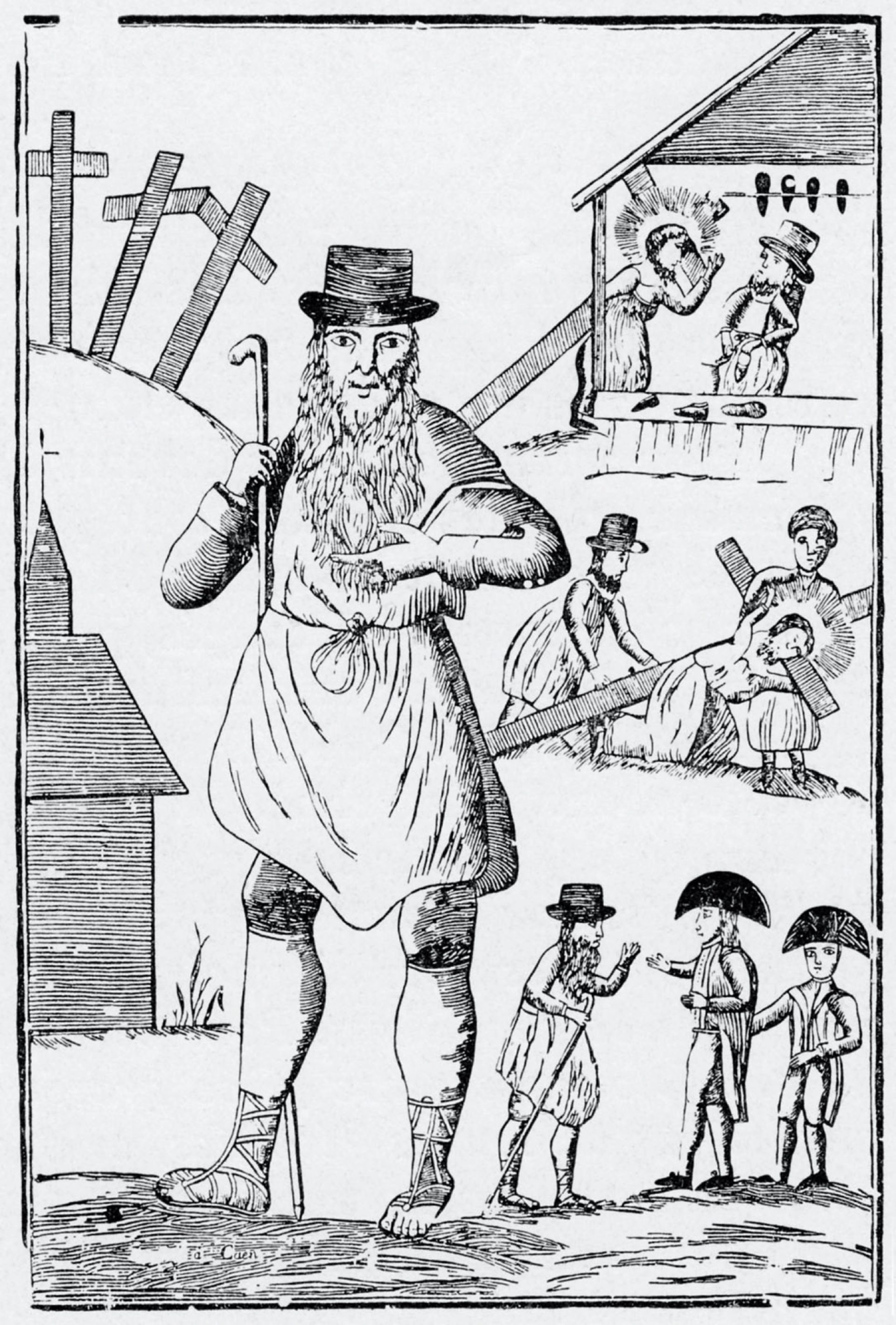

Conversely, this also means that – whether we are dealing with antisemitism or “group-focused enmity,” anti-Muslim racism or homophobia – we are referring to a notion of humanity that was shaped 250 years ago and that forms the foundation of Germany’s Basic Law. The fact that scholarly comparison is not the same as “equating” is so obvious that it almost seems embarrassing to have to explain it yet again. In fact, differences become visible precisely through comparison. For example, when considering religious-based antisemitism, one sees that the two later monotheistic faiths – and particularly Christianity – sought to differentiate themselves from the “original” monotheistic faith: Judaism.

It was primarily the direct competition between Judaism and Christianity in the first centuries AD that played a role here, leading to waves of persecution, hate and murder. Jews were defamed as God killers, and their survival as the “chosen people” – in flagrant defiance of the Christian requirements for salvation – was explained by myths of their “secret power” and connections with evil forces. These conjured images of “Jewish power” morphed into today’s classic conspiracy myths, which depict Jews as all powerful, as secretly pulling the strings of the economy, politics and media on a global level like grey-bearded puppeteers – while at the same time subjecting Jews to hate-filled racist notions of cultural, social, and moral inferiority.

Racism and antisemitism

At the same time, the links between antisemitism and racism are quite obvious. Just consider current phantasmagoria like the “Great Replacement”, according to which “the Jews” are trying to weaken Europe through an “exchange of population”, deliberately attracting hordes of fecund migrants to the Continent while cleansing the Near East and Middle East of Muslims as a side benefit to Israel. As absurd as this may sound, it must be said that some allegations of Muslim power and influence have become very close structurally to the classic conspiracy theories. However, such theories can point to Islamist terrorism as evidence of a sudden threat emanating from people who have similar names or (consider the anti-Muslim attack in Hanau) who simply have black hair.

These are some of the chief talking points in the politically charged field of antisemitism studies. Of course we in the field have a wide variety of fundamental attitudes, assessments and positions. But what distinguishes, or should distinguish, academic work from day-to-day political instrumentalization is – in addition to something as banal as the language skills needed to read and understand one's sources – the ability for self-reflection and dialectical thinking. Or, to put it simply: Discrimination impacts people in different ways. But that does not mean that those who suffer discrimination are incapable of discriminating against others: Gays can be racist, Muslims can be antisemitic, Jews can be homophobic, and women are by no means all superior to men. That is not really so hard to understand, if one wishes to understand it.

Partner